|

Confederate JS Anchor Enfield P-56 Cavalry Carbine w/ Texas History |

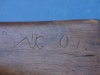

This is an rare Pattern 1856 Enfield Cavalry Carbine that is one of a small number made by EP Bond of London circa 1863 for the Confederacy. Over the years, I've had a number of these P-56 cavalry carbines and all have been either Birmingham-made Towers or London-made by Barnetts. This is the first one I've ever had by EP Bond. Best of all, it is JS Anchor inspected and a scarce variation at that. Unlike his earlier work, this carbine has Confederate viewer John Southgate's JS Anchor symbol placed ahead of the toe of the buttplate on the top of the stock instead of directly behind the trigger guard on the bottom wood; as found on earlier 1861-62 production Enfields. Another interesting aspect is that these late style JS Anchor Enfields do not have inventory "blockade" numbers engraved on the top of the buttplate. Texas history: Over the years, a handful of EP Bond carbines have surfaced in Texas including this one which was found there last year. In 2009, an article appeared in North South Trader magazine detailing three EP Bond carbines found in Texas. Two of these carbines were id'd including one to Confederate cavalrymen, one who served Company A of the 21st Texas Cavalry and the other who was in Company A of the 32nd Texas Cavalry. This carbine is very similar to those in the article as there is a great deal of Confederate graffiti on the stock in the form of initials and was appears to be the number "07" on the left side below the buttplate. Perhaps some in depth research might yield the identification of the soldier to whom it was issued. Note: The magazine and article will accompany this gun. In addition to that, there is some newly released information on these guns in the long-awaited book by Russ Pritchard and Corky Huey, The English Connection, which just hit the market. We were able to obtain a copy of this fantastic new book at the Baltimore Arms show last week and were stunned by the depth of information it contains. In it, the authors note that a small number of EP Bond carbines were shipped from England to Cuba where they apparently sat for quite some time before being run through the blockade in two runs into Texas at the end of 1864 and early 1865. These were probably run in through Galveston as this was the only Confederate port that could receive much of anything in the way of foreign supplies through the Union naval blockade after the fall of Fort Fisher and Port of Wilmington NC in Jan. 1865. Overall Condition is in NRA Antique Fair+ to Good Condition with a light gray patina on the metal and typical tan/blond wood which are both indicative of having come from an arid climate. London proofs on left side of the barrel are good and legible as are the markings on the lockplate. There are numerous contractor and sub-contractor stamps in various places including "BOND" underneath the barrel and inside the lockplate. Inside the ramrod channel are initials and the name "ALEXANDER" which is also seen on one or more of the EP Bond carbines in the North South Trader article. See photos. Bore is in good shape and still has its original three groove rifling intact. Wood is solid with no breaks or major repairs. After years of handling these Enfields, it becomes apparent that the Confederates often went to greater lengths to personalize their weapons than what we typically find with Union issued examples. Typical of many rebel Enfield Cavalry carbines, this one was deliberately "slicked" by the Confederate cavalryman it was issued to for ease of use in combat conditions. As much as collectors scoff at missing components, there appears to actually be a great deal of thought that went into this practice. It is my firm belief that these stripped down carbines were the direct result of first-hand lessons learned on the battlefield. Typically, this involved the removal of anything a soldier deemed could get in the way, snagged on his uniform/equipment, or slowed him down through extraneous movement during combat. Remember, when these were issued in 1865, there was nearly a 100% chance that any encounter with Union cavalry would mean putting this muzzleloader up against a breech-loading carbine such as a Sharps, Maynard, Burnside, or worst case scenario, a Spencer or Henry repeating rifle. He would have been acutely aware of this and knew that a few extra seconds of fumbling around with a paper cartridge, ramrod, or the simple act of untying his weapon from its scabbard could be the difference between life and death. Just about the only advantage he would have possessed with this Enfield P-56 Carbine was its range. In spite of its size, the Enfield carbine was accurate up to several hundred yards. Depending on the situation, this extra distance could buy him either time to get away or to reload before he was within range of his enemy. However, for the most part. after the first shot of an engagement, he would be at a huge disadvantage against almost any Yankee breech-loader in reloading. For close quarter situations, he would have relied mainly upon a revolver, perhaps a sword (which were largely discarded by the end of the war), and if all else failed, his horse. With survival paramount, all the bells and whistles on this carbine had to go...and off they came which we have inventoried below: 1. For starters, to cut down on the time it took to reload, he discards the captive British rammer which was literally attached below the muzzle via a small cumbersome swivel. Given the vast number of these that are missing or have been replaced by collectors with reproductions, the Confederates must have loathed them. From the looks of it, he removed the swivel and either modified or replaced the original rod. As you'll note in the pictures, there is a small flat piece of iron pounded around the end of the rod to form a cylindrical knob which protudes out from under the muzzle. In my opinion, this gives the user something to grasp more quickly than had it rested flush with the muzzle. Also, one side of the knob is slightly flattened so that it rests firmly against the small block beneath the barrel where the captive rammer was once attached. This would have speeded up time to reload. One of the carbines pictured in the North South Trader article goes even further to ease the loader's ability to grasp the ramrod. Not only was the captive rammer removed but the forend cap and wood cut all the way to the front barrel band. See photos. 2. Another thing he did, which again was very common on Enfields, was to remove the rear sight. These were not held by screws but silver-soldered to the barrel. As you'll note in the photos, there are marks on the rear edge of the small square pedestal where the rear sight once rested. These are from him prying it off the barrel...this was NO accident. There are several different reasons this could have been done but one was that ladder and leaf sights were highly ineffective when the distance from the enemy was misjudged...which was easy to do in combat. One story I read concerned the capture of a number of "Yankee" Enfields at the battle of Pickett's Mill near Dallas, GA in 1864. Balls were noted as "sailing over our heads and into the trees behind the lines" during the battle. Upon capturing the Union position some 300 yards away, it was discovered that the ladder sights on their Enfields had been set for 500 yards causing their shots to harmlessly pass over. Upon capture of these rifles, it was duly noted that these sights were quickly removed so as not to cause any more confusion. Most of these men grew up on farms using rifles with either fixed sights or no sights. The fact that the Confederacy produced very few rifles with adjustable sights gives an impression that this sentiment went well up into the upper ranks. Other reasons for this would be to prevent the gun from snagging in its saddle scabbard or on clothing while being wielded on horseback. Once again, one of the three carbines featured in the North South Trader article shows it too, has had its rear sight removed. The other two EP Bonds simply have the rear sight block with the yardage leaves missing or removed. 3. The saddle ring has been removed and the sling bar purposely cut or filed off. See photos. Of the three EP Bonds in the article, one carbine has the exact same modification...bar and ring removed, while another carbine simply has the bar present with no ring. This is perplexing as the ring and bar were there to keep the carbine either tethered to a saddle scabbard or clipped onto a shoulder sling during transit on horseback. However, maybe that was the problem. You're riding when trouble arises and you can't get your carbine untied from its scabbard in time. Furthermore, the rings did rattle and could make enough noise to spoil any element of surprise. With Winchester saddle ring carbines, it was common practice to either remove the ring or wrap it in leather while hunting deer. The same could probably be said here. The removal of the saddle bar took this one step further. If you're ever picked one up before, that protruding saddle bar adds quite a bit of bulk and extra width at the center mass of the gun making it harder to grasp. Removal improved one's grip and prevented it from being tethered to anything forcing it to be kept at the ready across the saddle or in hand. I have seen this modification on so many Enfield carbines that it is almost as common to not have the saddle bar and ring as it is to have it in place. This is one of the few examples of Confederate items I've seen from the far western theatre of the Civil War that saw use with some of the last remaining Confederate units of the Civil War into mid-1865. Item# 1812 SOLD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|